The Innovators: An Australian and Ethiopian Team Fighting Leishmaniasis

My parents taught my brother and me to be resourceful and creative from an early age. We knew growing up that we couldn’t really afford the newest and best, but we could always make do with what we had. We were fixing things instead of throwing them away and always finding ways to make something last for as long as possible. While often annoying and inconvenient for me, my little family seemingly could get any issues around the house fixed and as a reward would get that sense of accomplishment that doing it ourselves was always better than buying new (or so my parents told us!). From this I carried away a sense of resourcefulness and creativity; solving problems with what I had and thinking that there is always a way to solve problems no matter how difficult or challenging. These traits connected with my love for technology and through an interesting journey I find myself working with the New Venture Institute at Flinders University as head of the Flinders Innovation Centre focusing on creating new products, tools and inventions for students, researchers and local businesses.

I was first introduced to Dr. Endalamaw Gadisa, microbiologist at Armauer Hansen Research Institute in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Andrew Nerlinger and Lisa McDonald, Co-Founders of PandemicTech, through my previous director of the New Venture Institute at Flinders University, Matt Salier, who sent me a brief email about this project. The project in particular called for a design of a new testing apparatus to help doctors rapidly diagnose cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) through a micro-culture method that has proven to be quite fast, accurate and cost-effective compared to other tests. For those who are unfamiliar, Leishmaniasis is one of the top parasitic killers in the world but often forgotten and categorised into the “neglected tropical diseases”. Presented with plans on the kit I took on the challenge to create this test kit through a combination of digital 3D CAD modelling, 3D printing and lots of patience.

The work that we do within the New Venture Institute focuses on helping startups and small/medium businesses rapidly develop new products and services. Our core is developing capability within businesses to think differently and out-of-the-box about how they approach challenging problems and to test new ideas with the people that are actually going be using their products. A totally different world from leishmaniasis, but I found strikingly that the method of approaching this problem is also similar to how we solve business problems — “Why is this important and who cares? How does it need to work to be successful? What would success look like?” Our lab in the FIC hosts a number of advanced 3D printers, manual hand tools and other equipment — perfect for rapid prototyping small projects but in this case, I needed to be real creative with the tools and resources I had accessible for this project to work.

Armed with these tools and strategies it took me a good 3–5 months bouncing around designing, 3D printing, testing, iterating and refining the prototype design before I was confident in sending over a test kit to Addis Ababa as the Generation 1 test kit. Fortunately, Leishmaniasis isn’t commonly found on the Australian continent but unfortunately each test kit would need to be sent through to Addis Ababa for testing with CL samples. I needed to make sure that these kits we sent to Addis Ababa would have the best chance of working. About a month later, I received news that unfortunately, the test kits didn’t work — total failure as the parasite wasn’t able to survive inside the kit for analysis long enough. I was hopeful that it would work the first time but would have been incredibly lucky if it had worked the first time!. I took the data and feedback that was given and started to work on the second generation of the test kit.

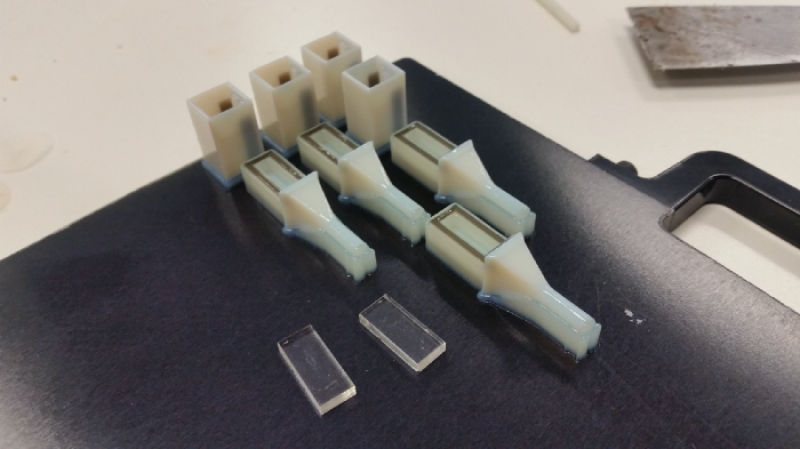

After thinking about how we can actually do something like this, the design of Generation 2 as a thought bubble about two months after the Generation 1 test results came back. With a new concept I immediately started working on a number of prototypes to prove that this new design could work. Data from the test suggested that the 3D printing materials we used were killing the parasite so the new design had to ensure that the parasites had a higher chance of survivability over the testing phase of a fortnight. There were over 20 different iterations with development focusing on clinical useability, sealing the unit from leaks and improving visual clarity for sample monitoring under microscopes. With the help of PandemicTech and Dr. Gadisa we were able to create new test kits to be sent through to Addis Ababa for lab testing with CL. It was early 2019 was when Dr Gadisa’s team tested out the new kits with limited success — but success nonetheless with room for improvement! With more data to prove that the 3D printing material maybe the reason why the tests were failing I went ahead and started the development of the Generation 3 test kits.

Generation 3 removed any 3D printing in the actual test kit and through the creative use of tools available to us in the lab we were able to create a totally new test kit that was even simpler and cheaper than the 3D printed variants. After a few weeks of fabricating and finessing a new set of test kits I sent them through to Dr Gadisa’s team. After a month I received news that the test kits had actually worked under lab conditions! Fully visible under microscope and the parasite was able to culture inside for over 2–3 weeks without perishing. What a satisfying moment that was. We are currently developing new iterations of the Generation 3 design and working out a pathway to manufacture another set that would be field tested with patients suspected of CL.

While this journey is still in progress, I can’t help but feel joy and excitement while working on this project. I value life very highly and the fact that this project can potentially save lives is something worth struggling and persevering for. I can definitely say bringing both creativity and resourcefulness to the mix has enabled us to push through some tough setbacks and has allowed us to pick up where it seemed too difficult to progress. We famously say “Fail Fast, Fail Quickly” as a way to get a new product out to market and by embracing failure, being resourceful, being creative and always pushing boundaries it’s possible to do something that no one has done before. My hope is that this test kit would become the standard test kit to test CL and that these be used to rapidly diagnose patients and start their treatment sooner; potentially saving them and improving their quality of life along the way.

About the Author: Raphael Garcia is the head of the Flinders Innovation Centre at the New Ventures Institute, Flinders University, in Adelaide, Australia. He holds a degree in Mechatronics Engineering from the University of Adelaide.